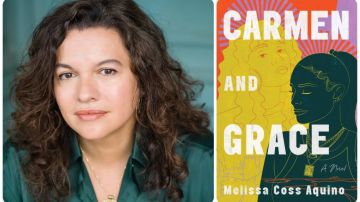

Melissa Coss Aquino’s New Novel Centers on Latina Sisterhood in the Bronx

Puerto Rican educator and author Melissa Coss Aquino knows the power of storytelling and the significance centering Latinx culture and characters

Photos: Courtesy of Melissa Coss Aquino, Cr. Nina Subin; William Morrow Books

Puerto Rican educator and author Melissa Coss Aquino knows the power of storytelling and the significance centering Latinx culture and characters. Her debut novel, released April 4, Carmen and Grace follows the lives of the book’s titular characters who are more like sisters than cousins, bonded by a childhood of neglect, addiction, and instability, and later, by the kindness of their benefactor Doña Durka, who also happens to be the leader of an underground drug empire. When the Doña suddenly dies, Grace is primed to take over the business, while Carmen is ready to leave and start a new life before her secret pregnancy reveals itself. But it might be harder than she thought to abandon the only life she’s ever known, her tight sisterhood with the other women mentored by Doña Durka, and Grace, whose plans are both reckless and threatening and may endanger them all.

“The book came to me when I was very young at 23,” Aquino tells HipLatina. “But it was a book that I didn’t feel ready to write from the perspective that I wanted to write it. It was a dream of maturity I wanted to have.”

She shares that it wasn’t until her late thirties while in graduate school with two kids and a full-time job that she decided to join NaNoWriMo, an annual campaign hosted every year in November that challenges writers to write a novel in a month. She did it “as a way to see if this book that had always been haunting me had anything to say. And when Carmen showed up on day one, it all just started pouring out. I had no idea that it would take another 10+ years to actually finish but that’s how I knew I was ready to start and do the writing.”

Before diving deep into the writing process for this book, Aquino kept busy with other projects including writing a different novel and going back to school for her MFA and later, her Ph.D. As she furthered her academic career, she spent her summers going back and forth between working on the novel and studying for exams, which made the writing process longer than is perhaps usual for many writers. But as she explains, she isn’t “a one-project person,” and the novel was worth taking her time on.

“What kept me going was the story itself and the characters and the spiritual journey that the book became for me as a writer,” she says. “I began to see that I had so much to learn about how to craft and how to shape scenes around these lives. It was exciting to me to see how I could express the perceptions of my lived experience inside of characters that I loved and were also informing me, demanding to do and say things I was not always comfortable with, and I felt very haunted by them. Alice Walker talked about how she felt like the ancestors were talking to her but for me, I wanted to honor and reflect on what it means to be part of a community that is in many ways under attack and yet has a great deal of courage in facing the conditions that they’re living.”

Black women writers like Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, and Maya Angelou were integral to Aquino’s beginnings as a reader and writer. Especially as a young child being raised by a grandmother in the Bronx who preferred her to stay inside and read to the point that if she was reading or just had a book open in her favorite spot in the window by the fire escape, her grandmother wouldn’t ask her to do chores around the house. But oddly enough, though she loved reading, most of the books she had access to were old-fashioned novels about life in the rural countryside or middle-class suburbs or Nancy Drew mysteries, which she couldn’t relate to at all as a Bronxite. Then, she read one book that changed everything. Ludell by Brenda Scott Wilkinson, which she mentions in Carmen and Grace, is about a young African American girl being raised by her grandmother.

“There’s this moment in the book where the grandmother’s putting Vicks VapoRub on her chest and I’ll never forget it because I could literally smell it. I didn’t have any on me but I was like, ‘This is what my grandmother does.’ In the end, Ludell wants to be a writer, and it all suddenly gave me a new experience of reading. One that’s a window out into a world very different from yours that gives you an opportunity to see a world you might not see. It gives you hope and faith where you feel mirrored and see yourself in a valued way. That really stayed with me.”

From then on she was motivated to write starting as early as third grade though it was in high school when her writing blossomed. She credits her teacher, Jaime Manrique, with recognizing that she is a writer and she needed to build a life for herself so she could sustain a writing career. “That’s when I really became a writer, even though it took me so much longer to get published and get involved at that level because I really started writing with the intention. I was going to write and it would be a part of my life and everyone would see that that’s what I do.”

But there’s one more part to her origin story that Aquino holds close and dear to her heart involving Wilkinson, who still lives in Georgia today. Prior to the release of Carmen and Grace, she reached out to thank the author for the radical effect she’d had on Aquino as a child. This led to a whole host of email exchanges, which are still ongoing, as well as Wilkinson reading Carmen and Grace and the women organizing an event in Georgia where they will interview each other in celebration of the novel. To say this is a full-circle moment for the books is, as Aquino says, an understatement.

In this way, it was Black women writers who shaped and molded Aquino as a writer in the early beginnings but things changed again later in her life when she began reading Latina writers like Gloria Anzaldúa in college.

“It shook me awake. It made me realize that you can tell a story about your place and your people, and you don’t have to reference anybody else or how anybody else is seeing it or how anyone else would experience it, because this is your story to tell,” she says. “It was open permission to say, ‘These are my stories and this is what I’ve seen and this is what I know and this is what I want to express to the world.'”

It’s no wonder then that Latinas are front and center in her novel in all their beauty, power, and complexity. As different as they are, Carmen and Grace represent essential parts of Aquino’s life and experiences, as well as the vibrant cast characters in her real life that led her to write the story in the first place.

“I love the courage that they have to keep loving – loving each other, loving the Bronx, loving their memories of their own childhood, and the persistence of that affection for each other and for their own lives, however they may seem as compared to others. That was key because I felt such a distinct calling from a very young age to recognize that I was being told things about myself, about my parents, about my life, about my family by other people or outsiders, that I didn’t think were the whole truth,” she says. “The same is true of spirituality. Some people had a negative relationship with it but other people had a positive relationship with it, and I really absorbed all of it and felt it in ways that not everyone in my family did. So Grace relies a lot more on her spirituality to carry her through, while Carmen just wants some tangible safety in the world. Both felt very real to me.”

The book’s setting in the Bronx acts as its own independent, unique character. The New York City borough has a largely Latinx population (56.4 percent) and is one of the counties with the largest Latinx population nationwide, according to the Pew Research Center. Aquino has published several essays about the Bronx and her own personal relationship to it and has been continuously working on several new full-length projects about the borough throughout her novel release. These projects include a nonfiction book for the Center for Puerto Rican Studies and a novel about three characters’ connection to the Catholic Church that’s taken over by a cult, going back and forth between the Bronx and Latin America. She’s also working on writing the story of her family arriving in the Bronx from P.R. told from the perspective of the land with larger meditations on migration and memory.

With Carmen and Grace, it’s no different. Her love for the Bronx practically bleeds off the page in the spots the characters gather in the community, the relationships they each have with their home, and the ways they talk about the Bronx. Ultimately, through these vibrant characters that she has brought to life, she hopes she can bring some much-needed humanity and fresh representation to Latinas and the Bronx to an industry where it’s still lacking. As she continues writing, she hopes she can be part of the change alongside the new generation of Latina writers from all walks of life, with her own unique twist on what matters to her and the place she comes from. She notes:

“Two things can be true at once. There are crimes and yet we’re also the greenest borough in New York City. We have the biggest parks, the biggest beach, we have it all. I want people to know that lives are led in every single place where people only focus on the crime,” she shares. “Those lives are complex. They celebrate, they laugh, they love, they come together. And like many other communities under siege or experiencing a lack of resources, which is the only problem that the Bronx has ever really had, it goes through these periods of disinvestment, then reinvestment. But I’ve lived the vast majority of my life here and it’s a beautiful place to live and a lovely place to visit. That’s what I would love for readers to get about the Bronx.”