Ari Tison’s Debut Novel Explores Generational Trauma & Healing Within Indigenous Culture

Young Adult novel "Saints of the Household" spotlights Indigenous Bribri Costa Rican culture

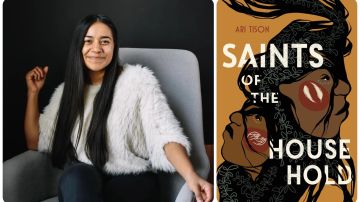

Photos courtesy of Ari Tison; Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR)

Ari Tison is a Bribri (Indigenous Costa Rican) American and African-descended poet, artist, and young adult author whose work is centered on the various forms of storytelling. Earlier this year in March, she published her debut young adult novel Saints of the Household, which follows Max and Jay, two Bribri American brothers who have always depended on each other for survival in the face of a physically abusive father and struggling mother. One day in the woods, they stumble upon their friend Nicole in a heated argument with her boyfriend Luca, the school’s star soccer player. When they come to her aid, they end up beating him to the point of being unrecognizable, sending shock waves through their small Minnesota town Deer Creek. As they grapple with how this act of violence has changed their views of who they are and their dreams for the future, they realize that it is only by returning to their Bribri roots that they can find a path forward and alter the course of their lives. Told in alternating perspectives, the novel offers poignant insights about abuse, trauma, brotherhood, and reconnecting to your roots, all told through a unique blend of short vignettes and poems.

“I’ve always been interested in storytelling and how it shows up in different ways, whether it be poetry or fiction or prose,” Tison tells HipLatina. “I especially love vignettes. I love novels that were written in different ways. Those kinds of books connected with me and they seemed to work the way that my brain worked. Saints ended up being a conversation of all those things that I loved into one book.”

Storytelling, she explains has “always been a big part” of her life. As a child, she loved writing short stories, especially fan fiction about the books she was reading at the time like the Chronicles of Narnia series. But she explored other forms of self-expression from an early age too, like acting, filmmaking, and art, which she still pursues today as a self-described “amateur painter.” Only later in life in undergrad and grad school did she discover how much she enjoyed writing poetry and fiction. On top of that, she learned how to blend these mediums in different ways, turning into novels in verse and “vignettes,” a brief descriptive piece of writing that captures a singular moment in time and focuses on specific details, themes, and imagery. In embarking on the journey of writing Saints, she was following the lineage of books like Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street and Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X, not only because they are both writers and poets she admires but also because she felt personally reflected in this format.

“Vignettes capture the heaviness of a traumatized brain or somebody who has endured trauma, and I’m one of those people,” she explains. “Those kinds of memories and spaces, whether they be good or bad or complicated, they tend to be pretty tight. Even the best memories we have, if we were to summarize them, they’d probably be about the length of a vignette if we wrote it down. There’s an interesting punch that happens with that format.”

In showcasing the perspectives of both brothers, Jay serves as the vignette piece of the puzzle. He embodies the tradition of the Greek muse or scribe, offering concrete details about the attack and its aftermath, bringing the world to life, and honing in on small moments—like his mother cutting potatoes or his brother Max taking a breath—that he wants the reader to notice. These moments can take up an entire vignette, allowing the reader to slow down and watch the story naturally unfold through his eyes. For Tison, his voice, which naturally took shape in this way, was the first to emerge on the page because she felt it would easily guide the reader into the story as a familiar form.

But she soon realized that the book was too slim with just his side of the story. That’s where Max’s words came in, this time appearing as poetry. Throughout the novel, we go back and forth between the brothers’ different ways of interpreting the world around them, creating a powerful tapestry of poetry and prose to tell a singular story. The tricky part, as she explains, was how to separate their voices to avoid the reader getting confused about who was speaking when, as they’re not only close in age but also both boys and brothers who have grown up in the same house under the same circumstances. How could she show the ways in which they’re not the same? So to further differentiate the brothers, Tison made the decision to also make Max’s work less concrete and more abstract and thematic, especially as he’s a painter.

“He’s looking for distance between his family, so there is distance on the page and the ellipses are recognizing that throughout his work, connecting and disconnecting, trying to find room for himself,” she says. “That then exhibits something that’s going on internally. If it’s shaped like him, he’s trying to figure out who he is or trying to tell himself who he is. Or if it’s shaped like a door, what does that door mean? Is it an entryway or is it closed? All of a sudden, shape brings in these other kinds of metaphorical conversations.”

Throughout the entire writing of the book, Tison was open to these changes, responding to what the book needed to deepen its themes and characters. But one major development that happened to the story almost didn’t happen until Tison sold her book to her publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In collaboration with her editor, she focused on adding more plot points and ended up creating the character of Nicole, Jay and Max’s friend who is Anishinaabe (Indigenous to the Great Lakes territories) and who plays a central role in the story. Not only is she Jay’s confidant but also a point of tension between the brothers and Luca, as well as her own person advocating for indigenous justice and personal liberation.

In doing so, Tison was able to develop the brothers’ relationship to the land, to women, and to the plot that helps them realize the importance of being in touch with their Bribri roots like learning the language and hearing sacred stories. But she makes it clear that she didn’t do such a major rewrite alone, working with her relatives who are Anishinaabe to get a clearer picture of what she looked like and her last name. While it was “scary” at first to hear that her editor wanted to go in a different direction, in the end, it made the novel better and she came out of it learning more about the world and herself as a writer. Which, she says, is true for anyone who writes a story.

“I think every book is collaborative in some way because we all come from storytellers. If you sit at a family gathering, somebody’s going to be sharing a story from however many years ago. There are storytellers in all of our families and we’re always getting things passed down to us from other people. It doesn’t make who we are less important but it’s nice knowing that we come from a garden rather than bare land.”

Above all, she hopes that Saints can be a source of comfort, or a resource overall, for how to deal with violence in its various forms in our everyday lives, especially for Indigenous readers. We all have the potential to face and perpetuate harm but Indigenous communities experience unique circumstances and therefore have unique needs. Thanks to violent histories and a modern-day world that is still perpetrating those harms, indigenous groups are vulnerable to a vast array of problems like poor mental and physical health, substance abuse, poverty, lack of educational opportunities, loss of culture and traditional languages, and violence from outsiders and within the home. In depicting abuse through Max and Jay’s family, she hopes that readers will see the tools to advocate for their own well-being.

“Growing up in abusive spaces is one of those secretive things that can feel really difficult to share, especially as a young person who should be taken care of in a house,” she explains. “My big hope is that people can see themselves and see that somebody was able to speak out about it in a book. Books in my life influenced me to be able to empower myself because it’s helpful to see something play out in a book and be like ‘What could this look like? What would somebody say?’ There are different ways that we can think about and communicate difficult things.”

When she thinks about the landscape of publishing and how it has both supported and harmed Native writers throughout history, she’s grateful to be part of the push for more diversity and indigenous representation in the industry today, especially being from a community that has yet to be adequately represented in the mainstream. By publishing Saints, she knows that many readers will be hearing and learning about the Bribri people for the first time, which she hopes will be an invitation for other Native writers to tell their stories and for non-Natives to open themselves up to learn and read more.

At the same time, much like Max and Jay, when she finds herself caught up in the nitty-gritty of the publishing process and how she shares her work, she returns to her lifelong values of oral storytelling, which she notes has been around much longer than publishing and even the invention of the printing press. Especially when we think about how few Native writers are traditionally published every year (less than 1 percent in 2021 in the children’s genre), it’s easy to become discouraged when your stories are undervalued. But it’s also empowering to remember all the forms of storytelling that have come before us that are just as valid and needed and always accessible to us. She notes:

“Having a book is part of being a storyteller. It’s nice to have something physical to share or to have people read that I would never have met. Those are the things that are very magical and special about publishing in that space. But it also feels like another extension of the work that I’ve already been doing. I try to stay pretty grounded to the fact that I’m a storyteller and some of my things get published and some of my things don’t. I try to hold onto my work without the expectation that it’s going to be in a certain space and still hold it as valuable. That’s the way I try to walk, that it will allow me to write other books and explore other avenues of storytelling, too.”