The Difficult Reality of Life for Latinas in the Foster Care System

In the sprawling landscape of California, a diverse tapestry of cultures, languages, and backgrounds intertwine to form the fabric of society

Photo: Unsplash/ Anthony Tran

In the sprawling landscape of California, a diverse tapestry of cultures, languages, and backgrounds intertwine to form the fabric of society. Among these vibrant communities is the foster care system, where countless stories of resilience and hardship unfold, the plight of Latinas stands out as a significant yet often overlooked challenge. The foster care system can be a daunting journey for any child, but for Latinas, their struggles are often amplified by several distinctive barriers. From legal and immigration status to language disparities and perpetual stigmas, Latinas face an uphill battle in their pursuit of permanency and stability.

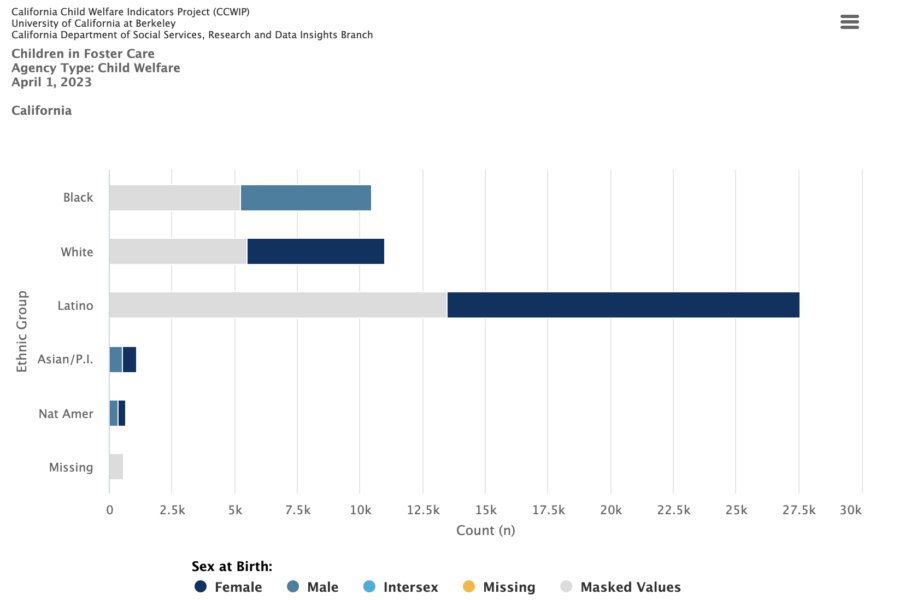

Based on the latest United States Census data, Latinxs make up 40.2 percent of California’s population, surpassing the white population at 35.2 percent. This demographic reality echoes in the foster care system, where a report from the California Child Welfare Indicators Project at UC Berkeley, as of April 2023, reveals a staggering figure of 14,103 Latinas in foster care, making them the largest group in the system, compared to 5,503 white non-Latinas. Moreover, Los Angeles County, the state’s most populous county, accounts for over 60.5 percent of underage Latinxs in foster care as of June 2023, according to the latest monthly fact sheet.

Latina and Native American Jacqueline Robles, 24, grew up in the LA County foster care system. Her journey began in 2004, at the age of five when she, along with her two older siblings, were removed from her parents’ care due to their struggle with drug addiction and mental health. She spent over 15 years in foster care, through kinship care reunification, with her maternal grandmother of Native American descent, from ages six to 16. The Department of Children Family Services (DCFS) made it challenging for her grandmother to gain custody, demanding specific housing requirements that proved difficult to meet. Jacqueline expressed her disconnection from her grandmother during this time, a consequence of her grandmother’s unyielding work to meet the strict criteria. “They (DCFS) wanted her to have x amount of rooms, and an x amount of the size of house and all of this before she could try to get custody of us” she tells HipLatina.

“A lot of us are not earning a living wage so this translates into not being able to get an apartment because you’re not able to afford it, so my grandma really struggled during this time and I don’t even know how she did it. She didn’t have credit, she wasn’t rich or anything but she had to do all that work before she could get custody of us, which is a challenge itself, ” she adds. “Something that I think people of color, especially Latinos face if they’re being paid under the table, or not having credit and not being able to get that approval for that apartment”.

When Jacqueline turned 16, her grandmother remarried and due to her step grandfather being physically abusive toward her, she re-entered the foster care system until she aged out two years later. Jacqueline’s struggles to find adequate living conditions are emblematic of systemic disparities that hinder Latinxs prospects for a stable life after foster care.

“Honestly, throughout all this adversity and barriers I just keep my eyes on graduating high school I knew about the statistics of kids in the foster care, I saw my peers fall victim to drugs, homelessness and incarceration and ditching school,” she explains. “I don’t want to end up like my parents, I want a better future for myself I want to go to college because that’s the way I see myself make a better future for myself.”

When it came to finding someone who shared their ethnicity and foster care background, she did not have such a mentor, making her journey through higher education somewhat daunting and uncertain. “When I was in the group home there was an educational specialist that was Armenian, he was the only person of color there and he really helped me a lot.” Although not having firsthand experience with foster care, the specialist’s understanding of the challenges faced by people of color in pursuing higher education provided valuable guidance she says.

Leaving foster care without permanent, legal connections to family or caregivers can lead to a multitude of challenges, from homelessness to economic instability. The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s latest report revealed a stark truth: 69 percent of Latinxs age out of care in California without a permanent familial connection. This statistic is a striking reminder of the uphill battle faced by Latinas seeking a sense of belonging and stability beyond the system.

Jacqueline fears that preconceived notions might affect her chances of a fair assessment in her career and shares that she’s an “open book” and there’s no shame but rather pride in her story despite the difficulties. However, in her younger years, she did experience a sense of shame about her foster care journey, not comprehending the complexities enveloping her situation. Surrounded by traditional family structures, she felt different and struggled with accepting her unique background. Fast forward to today, and she’s received her master’s in public policy from UCLA and her calling lies in policy creation and change, envisioning a future where she can impact federal policies that trickle down to uplift communities like her own.

Apart from her full-time job as the Inclusive Economic Development Advisor at New Growth Innovation Network, Jacqueline engages in informal mentorship, becoming a source of inspiration for those in foster care with similar backgrounds or circumstances. She hopes to show them that with determination and hard work, they can achieve anything they set their minds to, breaking through barriers and realizing their dreams.

“I hope that my story inspired others to choose differently and make a better and different life for themselves, especially for those that may have come from similar backgrounds as me. You don’t have to be the outcome of your background, of your parents and you are the author of your own story. So you can do whatever you want, I just hope my life and actions inspire others to do the same in this world.”f

Xiomara Torres, 51, is a Salvadoran Circuit Court Judge at Multnomah County Courthouse in Portland, Oregon. Motivated by her experiences as a Latina navigating the foster care system, she aspired to break barriers and pursue prestigious professions traditionally dominated by non-diverse groups. Her journey began when she was nine and fled the civil war in her homeland in 1980 along with her family. Fondly recalling her early childhood, she reminisces about the warmth and connection to her birthplace, where she enjoyed walks to the river and traditional village festivities. Her life took another turn at the age of 13 when she ended up in the LA County foster care system.

Xiomara reported sexual abuse in her home to the school, which subsequently led to her removal, along with her siblings. Throughout her childhood in foster care, she vividly recalls the constant upheaval, as she navigated through various placements, adapting and adjusting to the different homes and foster parents she encountered along the way.

Navigating these challenges proved to be difficult due to the constant changes. Moving from one school to another had a significant impact on Xiomara’s educational journey. The initial transition was particularly striking as she moved from an environment predominantly composed of Latinxs in East Los Angeles to one where the majority were white in Covina. Standing out in this new setting was unavoidable, and Xiomara chose not to disclose their status as a foster kid to many of those around her. As a result, adjusting to the new surroundings and homes became a crucial aspect of their experience.

For Xiomara, the intricate web of navigating the foster care system wasn’t the only worry she had as a minor, immigration paperwork added another layer of complexity to an already difficult process. She recalls that her mother and father were in political asylum, and they were also working on Xiomara’s residency application. However, once under the wing of the foster care system, her legal status adjustment were handled by the Department of Children and Family Services. She vividly remembers participating in interviews and visits to the immigration office alongside her case worker during her time in foster care, knowing that her legal status was an important aspect being addressed during this period. It was a layer of entanglement that only motivated her toward her path of becoming a judge.

In her early professional career, Xiomara had always been open about her story with people who were very close to her. But due to her work in the field as an attorney, she had to exercise caution and be discreet. She used to represent families and worked for the attorney general office that prosecuted cases.

“I didn’t really want people to think I was being biased in terms of the cases I was handling because I was in the field”, she shares. It was during her time as a judge that she felt more at ease sharing her story. When the governor’s press release mentioned her as a foster child, she recognized the significance of this information, especially for other foster kids who might come across it. She currently resides in the state of Oregon and in 2019 she was the spotlight of the play Judge Torres that showcased her journey from being an undocumented foster child to becoming a judge.

“I wanted students to get a really good sense of what the foster care experience would have been like for someone because they were watching that play and if they were foster kids in their school, they could be more compassionate, and have a little understanding of what that experience is like”, she says.

The driving force of Xiomara’s endeavors is a desire to give back to the community. Remaining in her current role allows her to actively engage in public service, a core value she has always embraced. Connecting with kids in foster care and motivating them to pursue education remains at the forefront of Xiomara’s vision for making a positive change in the world.

“I think the most rewarding part of my job is being able to be one-on-one with kids who are in care and who are going through it. Sometimes I have foster kids who just moved from one home to another and I say to them, ‘I know what that experience is like and it’s hard’ and I think just hearing it from a judge is so tremendously hopefully helpful”.

As California’s Latina population grows, it is crucial to shine a spotlight on the challenges faced by these young girls in the foster care system. The statistics paint a stark picture of disproportionate representation and the hurdles they encounter, from legal and immigration barriers to language disparities and stigmas. Jacqueline Robles and Xiomara Torres are living testaments to the resilience of Latinas, demonstrating their potential for greatness when provided with the necessary support and opportunities. By bringing light to these issues and amplifying stories like these, we can give the unheard voices the chance to overcome their struggles and pave the way for a brighter, more equitable future.