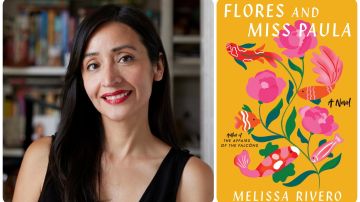

Melissa Rivero’s New Novel Explores Grief and Mother-Daughter Relationships

Melissa Rivero's "Flores and Miss Paula" explores the mother-daughter dynamic following the loss of the family patriarch

Photos courtesy of Melissa Rivero (CR: Bartosz Potocki); Ecco Books

Born in Lima, Peru and raised in Brooklyn, Melissa Rivero is the award-winning author of the 2019 novel The Affairs of the Falcóns whose work explores immigration, family, and the strength of the human spirit. This month, she published her sophomore novel Flores and Miss Paula, which follows the titular mother and daughter navigating their lives three years after the death of their husband and father, Martín, from cancer. Burying their grief below the surface, things begin to crack when Flores finds a note from her mother hidden beneath his urn, reading Perdóname si te falle. Recuerda que siempre te quise. (“Forgive me if I failed you. Remember that I always loved you.”) As Flores tries to understand what Paula would need forgiveness for, newfound doubts, memories, and resentments return in full force, worsening when they discover that they will be forced to move from their Brooklyn apartment. With one last chance to find common ground, Flores and Paula must learn to let go of their expectations for the other woman, confront their past, and decide if their vision for the future looks the same. Told in alternating perspectives, this is a tender novel that views its protagonists with empathy, compassion, and humor.

“Grief is a big part of what I write, whether it’s a diasporic grief or an intimate personal grief because it’s something most of us can relate to,” Rivero tells HipLatina. “Society at large tells you that it needs to be in the back of your life, whereas I feel that if we learned to live with it and alongside it, it wouldn’t be so crushing and devastating at times.”

Though writing has only just become a major part of her life within the last few years, storytelling has always been Rivero’s passion. She remembers writing her first poem in Spanish when she was five or six years old, going on to write short stories that would win prizes in school. Teachers believed in her so deeply that they were the ones submitting these stories on her behalf, encouraging her to continue wielding her pen. But at home with her family, it was a different story.

“As a good immigrant daughter, I had to go to school and study and focus on a professional career that was more practical,” she explains, leading her to put aside her creative dreams, at least for the time being.

Rivero decided to go to business school, working in advertising before going to law school. While an obvious draw was the potential to make money, she also had hopes that she would be able to use that education in law to help her community, support her family, and pay off her growing student debts. At the time, she saw a far more meaningful career in law than in advertising.

However, her life changed again when she began working at a law firm and her father got sick from cancer, similar to Flores’s father in Flores and Miss Paula. Spending her days between the office and the hospital, she quickly became exhausted but didn’t take a lot of time off even after her father passed away, determined to move on even with the grief still fresh and palpable.

“Much like Flores, I went back to work because I wanted things to go back to normal,” she says. “But there is no normal after you lose someone so meaningful to you. There’s a shift that happens and in some ways, it is our responsibility to acknowledge that shift, even if our inclination is to ignore it. It’s a survival tactic in many ways because we don’t want to acknowledge the pain or accept that that person is gone. How do we move on from that?”

If nothing else, her father’s death was a wake-up call, “the universe slapping me around” to take meaningful time off work and do the things that brought her joy, which in her case was dance and writing. From belly dancing to hip hop to tango, she poured her grief into physical movement, signed up for a writing class, and applied to the writing residency Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation (VONA) for BIPOC writers. It was there that she crafted that first scene of what would become her debut novel The Affairs of the Falcóns, kickstarting a thriving writing career that has continued through two pregnancies, temporary return to legal work, and absence from the law as well.

Interestingly, her sophomore novel began in a very similar way to Affairs, from a scene she wrote in response to an exercise during a short story writing class. The scene would end up being the first scene in the novel where everything begins to shift in Flores’s world from the very first sentence: “I find the note under my father’s urn, on the morning that marks what would have been his sixty-third birthday.” From there, we’re off to the races in her and Paula’s worlds, their views of each other, their memories of Martín, their grief, and something tense beneath the surface ready to shift.

Initially, Rivero believed the novel would be told entirely from Flores’s point of view. Her mother Paula would have a smaller part to play and her daughter would be instead on a lone journey of finding real, tangible success in her life. But there was a voice in the underbelly of the first draft that she couldn’t ignore.

“I kept hearing a lady in my ear criticizing her, not doing it in a mean way but like when you’re at a party and you’re sitting next to your tia on the couch and she leans over and whispers to gossip,” she says. “As I started to listen to her, I realized that she was talking to herself but also saying things to her daughter that she couldn’t say before.”

What ended up being unearthed was a practical millennial daughter in Flores, who shows her determination, focus, and stubbornness many times throughout the novel, all while thinking about what else her life could look like on her own terms. Paula, meanwhile, has many expectations for Flores, including marriage, but she also has her own separate life of adventure and risk-taking, even if she holds back at the last moment. It’s a complicated mother-daughter relationship at the heart of this story but as the reader unpacks the threads of the past along with them, it’s clear that there is still deep, pulsing love.

In some ways, Rivero’s sophomore novel was easier than her debut. Spending half an hour on it every morning, she found that was far better at revision, editing herself as she went along. But perhaps one of the biggest challenges she faced was not accounting for the opinions of the publishing world, much less the public, as there would be inevitable comparisons that would be drawn between her two books, and even more so with her current third work in progress.

“Maybe they’re all made up but there are certain expectations that you have for yourself and that your publisher and agent have for you,” she says. “When you’re a debut, there’s nothing for them to base their investment in you but it’s different with a second book because you have those sales numbers from the first. So the expectations are elevated and it’s hard to not have that in the back of your mind as you write. But I need to be faithful to the story.”

More than anything, she hopes readers take away important lessons she herself has had to learn about grief and how we balance our love for the deceased and still live meaningful lives. In writing Flores, she of course experienced the joy of writing a second novel to build upon her first and shape an important body of work. But as with her debut, she also learned important aspects of herself along the way.

“I realized that there was a lot of grief that I didn’t want to tackle. Sometimes it was difficult to write because it felt like I was opening up old wounds. I don’t know if it’ll ever feel okay but I did learn that it’s okay to be vulnerable and acknowledge the pain. You don’t always have to push it aside.”

In terms of a life outside of writing, Rivero’s career in law has been in limbo since selling Flores to her publisher and leaving her job. There are still many questions she has when it comes to how and when she will return to work. And while she knows it can’t be forever, it’s clear that she’s enjoying a life of writing: promoting this novel on her book tour, writing a third, and chasing creative work full-force. But no matter what ends up happening in her life, writing and telling stories has become her ultimate salvation, the thing that’s there when there are inevitable changes in her life, the thing she always returns to. It is, without a doubt, her greatest love. She notes:

“I love storytelling so much. I love it when something stirs my soul. I love reading things that make me ask, ‘How did this person do this?’ I love books that make me want to throw them across the room because it’s so good and inspires me to step up my game as a writer. It’s this way of escaping and creating something that feels beautiful to you and that you hope others will feel as well.”