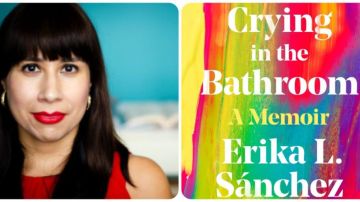

‘Crying in the Bathroom’ by Erika L. Sánchez is the Liberating Memoir Latinas Need Right Now

Acclaimed author Erika L

Photo: Adriana Diaz/Penguin Random House

Wearing a lime green Mexican embroidered huipil against a turquoise painted wall adorned with Chicana art, Erika L. Sánchez, the Chicago-based Mexican American writer, wears her heritage on her sleeve as she speaks to HipLatina about her captivating new memoir Crying in the Bathroom out July 12. The New York Times bestselling author of her debut novel I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter has once again written a book that speaks to Latinas that have had to wrestle with the dual pressure placed on us by society and our families to be something other than what we are. Crying in the Bathroom is a manifesto that gives language to the Latinas that want to break free from the shackles of perfection and who are unafraid to embrace their ambition, sexual desires, and so-called imperfections.

Sánchez tells us that the process of starting the book began about seven years ago as an essay about ambition. “I felt something loosen in my spirit. Writing the truth felt really hard and cathartic at the same time,” Sánchez says about what that essay transformed into. The truth-telling motivated her to embrace the memoir as her next project following the success of her first book, which is currently being developed into a feature film directed by America Ferrera.

Inspired by women of color writers including Gloria Anzaldua, Sandra Cisneros, Toni Morrison, and Samantha Irby, Sánchez’s memoir is a blunt and, at times hilarious, reflection of her experiences with sexuality, depression, and self discovery. Sánchez set out to write a book that could be “in conversation with” writers like fellow Chicagoan and Mexican American writer Sandra Cisneros and she accomplished it in this must-read memoir worthy of the Latina literary canon.

Sánchez’s writing is liberating with an opening chapter centered on the years-long saga she faced trying to cure her vagina of persistent discomfort that perplexed both her and medical professionals. Sánchez compares this opening chapter to the opening of her novel, as a “punch in the face” that doesn’t waste time to tell the reader what they’re getting into. “That’s just my sensibility where I want the reader to know what’s going to happen. This is going to be real,” she says. Though not a sequel to her novel that centered around a teenage girl and her own identity struggles, Sánchez describes this memoir as the next chapter in a young woman’s life. What follows is a front-row seat into Sánchez’s early sexual life navigating toxic romantic relationships, across continents, while dealing with multiple misdiagnosis and treatments for her vagina.

When Latinas are disproportionately dying from treatable diseases because of cultural stigma about vaginal health, an entire chapter on the subject feels revolutionary. What Sánchez does in this memoir is free Latinas from the shame many of us carry when discussing our sexuality. “I am so tired about the shame around being a woman and having a vagina, not that you need a vagina to be a woman. The vagina has always been a sight of filth and shame. You’re not supposed to talk about it. You’re a whore if you have sex before you’re married. That discourse is so boring and old. I’ve had enough. There is no reason to keep shaming women for existing in their bodies.”

Continuing with the breakdown of stigmas, Sánchez gives a raw and honest account of battling depression throughout her life. Perhaps particularly striking is that she dealt with one of the worst bouts of depression during the time that her career was skyrocketing with the success of her novel. “It was a period in my life where I didn’t see the point of anything. I just wanted to disappear. People were demanding so much of me at that time. I had to cancel events and go to the hospital to try to get better. People got upset at me,” she says, recounting what it was like to survive this dark period in her life.

“People think success means you’re just happy and carefree and everything is great. That simply is not true. I still had all this trauma that I hadn’t dealt with and that I was going through. I want people to know that mental illness isn’t a choice, it’s not a character flaw. It’s not laziness. It’s a serious illness that impacts every part of your life. Success doesn’t cure it.”

Sánchez’s vulnerability in telling her experience with depression is a level of intimacy she’s accustomed to sharing in her books and on social media but that doesn’t mean she has no boundaries. She shares that people don’t often think about what a person might be going through and that her job as a writer is the sole focus. “I love that about myself and I love that about my life, but I am a human being, I go through stuff. I have challenges. I am a Mexican woman. I am taught to give everything all the time and I refuse. There are things that I don’t want to share.Things that are mine,” she says.

Among those personal parts of her life that Sánchez protects from the public eye is her baby daughter, who is both Black and Mexican, and part of her motivation to dismantle white supremacy in her writing and projects. The memoir addresses the subject of colorism and anti-Blackness in Latino culture, adding to the many taboo topics Sánchez tackles in this book. “I wanted to write about the origins of [colorism] so people can understand where it came from. It’s something deeply rooted in our history and it’s something that we can stop if we try,” she says. For readers that want to hear more ways that Sánchez is breaking down white supremacy, she recently launched a podcast, “No Chingues”, where she and her co-hosts harness the limitless power of Black and Mexican shit talking to go after white supremacy with the unearned confidence of a mediocre white man.

There is a familiarity in Sánchez’s memoir in the way she weaves in humor while discussing trauma, a coping mechanism that many Latina readers will identify with. “I realize that life is really absurd. I have to make fun of it, or else I feel consumed by it. I think Mexicans are really good at that, at looking at the humor in really uncomfortable and unpleasant things, about being poor, crossing the border. I grew up with these sorts of jokes about things that are really tough. I think I learned how to do that as a survival mechanism.” Sánchez’s humor pierces through this memoir with many laugh out loud moments. For example, in the chapter entitled “Back to the Motherland,” Sánchez writes “People often ask me where I am from, and when I say Chicago, they look perplexed. One man told me I didn’t look like it. I suppose he had never in his life been to Chicago, because, come on, I can throw my chancla in any direction and hit a nice señora who wishes me a good day.”

Most of all, Sánchez’s writing cultivates a sense of belonging for the millions of Latinas and women of color who find a rare opportunity to see themselves and their experiences reflected in a book. In writing about the duality of being the daughter of immigrants and the push and pull that comes from living within two worlds with an unsatiated hunger to give testimony to that experience, Sánchez speaks to a generation of women that are forging their own place in the world. As she writes, “When you don’t belong, you learn to make a nest in the unknown.” Thanks to writers like Sánchez, that nest of belonging is a little bit more formed for the rest of us who find a home in her writing. “I rather live in that strange little world that I’ve created than in a world that doesn’t accept me,” she says.