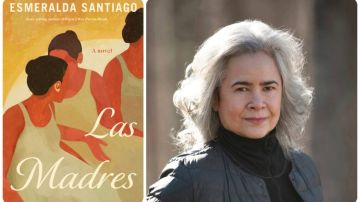

Esmeralda Santiago’s ‘Las Madres’ is an Ode to Puerto Rico and Sisterhood

Writer Esmeralda Santiago talks the inspiration behind her novel, "Las Madres" centered on a group of Puerto Rican women in the midst of Hurricane Maria

Who are we without our memories? That’s the question Puerto Rican author Esmeralda Santiago asks in her latest book, Las Madres. The story centers on 15-year-old Luz in Puerto Rico in 1975 who suffers a a traumatic brain injury that leads to memory loss. The timeline jumps between then and 2017 in the Bronx with Luz as a mother to Marysol who, along with close family friends Ada and Shirley and their daughter Graciela, as they take a trip to the island right as Hurricane Maria strikes. Throughout the novel, Luz’s real-life contrasts with her lack of memories and as truths are revealed las madres and hijas are in survival mode as Maria batters la isla. This novel marks her return after nearly 20 years since her last book was released. Santiago rose to fame in with her memoir When I was Puerto Rican (1993) about her childhood in Puerto Rico which became the first in a trilogy of memoirs that includes Almost a Woman (1998), and The Turkish Lover (2004).

“Having written three memoirs, I’m preoccupied with memory: who remembers what? Do stories change when the person who experienced tells it? How do those who observed or heard about the event talk about them? And who do memories belong to?” Santiago tells HipLatina. “As a novelist, my job is to convert concepts into dramatic scenes, and I endeavored to find moments and actions that revealed my intentions. Puerto Ricans love to tell stories, one reason some of the scenes are conversations between las madres, las nenas, doña Tamarindo, and others. They reveal the teller, and the story often changes depending on who shares it and why.”

Weaving together the different stories of each woman we see how the stories can shift and how memories (and the lack thereof) can impact each of them. But it’s not just the memories of the characters, it’s the memory of the island itself and its changes not only over time but in the aftermath of the hurricane which lasted from September 19-21, 2017, considered the strongest storm to hit the island in nearly 90 years.The Category 5 hurricane devastated the northeastern Caribbean and it led to the death of an estimated 3000 people. Santiago doesn’t shy away from painting a graphic and honest picture of the devastation of the hurricane.

“There was an aftermath that continues to affect Puerto Ricans there and here. I wanted to make sure readers, especially those who know little about Puerto Rico and its people, consider that we still struggle with the devastation,” she explains. “What happened in the weeks, months, years after the cyclone has and will continue to alter the present and future of the archipelago and its people. I wanted to make sure readers know the hurricane didn’t end when it whirled out to sea.”

In the Coda of the book, she acknowledges how Puerto Ricans are still coping with the aftermath of Hurricane Maria as well as Irma and Fiona. She opens up about the amount of research she did in preparation for the book and it’s evident as readers will find that the island itself is a character in the novel.

“To be a Puerto Rican wherever we are is to fret over the uncertainty of often violent weather, natural forces, and repressive political directives that have shaped us for more than five hundred years of colonization by Spain and the United States. Resistance has been constant and consistent, but unlike the other islands in the Greater Antilles, we’ve been unsuccessful in our revolutionary efforts. But one thing that’s true about Puerto Ricans, we do not give up. Nosotros no nos rendimos,” she writes in the Coda of the book.

“I write about Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans and deliberately use the archipelago as a character that affects and influences the protagonists and secondary characters,” she tells HL. “From the beginning, I knew the hurricane would be at the center, that the protagonists were connected, and where they would be at the end. The first scene I wrote didn’t make it into the final draft of the book: Luz, Graciela and Marysol on the roof, watching the fireworks on July 4, 2017. Once I had them in mind, I began to ask questions of them/myself: who are they? How are they related? How old were they? What were they doing on the roof?” she added.

As the story unravels, readers learn that each of the women have their own story and their secrets and pains and collectively we see how their union is both a means for healing and the cause of pain. Luz’s memory loss is part of what allows some secrets to stay secret and as these come to light, the turmoil amid the hurricane is equivalent to the emotional turmoil they face. But Santiago takes it a step further by exploring the secrets people choose to keep all while the reader is aware of what’s being shared and what isn’t.

“We all hold secrets: ours or those of others. We can know someone our entire life and never learn certain things they don’t share, either deliberately or because they’ve blocked it from memory. I wished to explore and add that aspect of relationships between friends and loved ones for each character,” Santiago explains. “I also like to give the reader information the characters don’t have access to, and when reading the novel, they’re in on secrets and information the protagonists don’t have. Again, this comes from my preoccupation over who holds memories, why, who owns them and whether, when, and how they share them.”

We see Luz speak in English, Spanish, and French despite her memory loss as the mind itself recalls what she doesn’t remember herself. We see her have episodes where she’s mentally somewhere else and we later learn the painful consequences of her trauma. But we also see her within a sisterhood with lifelong friends Ada and Shirley, their daughter, along with Marysol create a foundation that supports her throughout adulthood – las madres y las nenas form a united front that emerges despite physical and emotional fractures.

Alongside the power of memories she also explores identity and its complexities, specifically through Marysol who is described as a Puerto Rican from the Bronx who yearned to go to Puerto Rico. We see her deal with navigating being a Puertorriqueña born in the U.S. who is proud of her roots and her parent’s homeland. Marysol asks “is anyone one hundred percent anything anymore?” For Santiago, exploring this topic through Marysol was inspired by her own interactions with people feeling sad, conflicted, and/or judged.

“As I travel and meet Puerto Ricans from all aspects of life and endeavor, I’m told about the sadness and sometimes guilty feelings because they identify as Puerto Ricans who might not speak Spanish, or for circumstances, live afuera and/or have never been there,” she explains. “This is real for people from other places, of course, it’s the lament of the absent. I can’t imagine being able to write about being a Puerto Rican without addressing, exploring, sharing this lament with readers.”

Almost exactly 20 years after the release of her last book and nearly seven years after Hurricane Maria, Santiago emerges with a love letter to Borikén resilience and to the islanders and the diaspora alike. In its 322 pages she offers a peek into a brutal reality of what people endured and continue to endure on the island that’s so often overlooked in the U.S. while also exploring what it means to be Boricua. In the end, her hope for what the readers take from this novel is simple:

“I hope they learn something about Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans. I also hope they love las madres and las nenas as much as I do.”