My Uncle Immigrated to the States So We Wouldn’t Have to

Forty years ago, long before my existence, my future was already being paved by my uncle’s actions and sacrifices

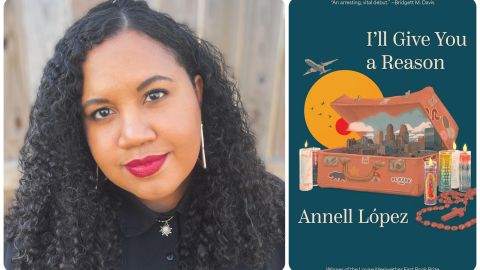

Photo: Courtesy of Johanna Ferreira

Forty years ago, long before my existence, my future was already being paved by my uncle’s actions and sacrifices. Forty years ago, my then 23-year-old uncle, boarded a plane in Peru and headed to America, changing the course of our family’s life forever.

My uncle, who we call Coco because his shaved head when he was young was shaped like a coconut, was in awe when he landed in Miami in 1979. With the sunshine came a freedom he could sense. With each gust of wind came an eagerness to discover new opportunities. But that feeling of childlike excitement only lasted a few minutes. Panic, confusion, fear, and anxiousness quickly overtook my innocent, pure-at-heart uncle who for the first time in his life was exploring the unknown.

Coco grew up in poverty. His mother and two sisters all slept in one bedroom in a house owned by my grandmother’s employer. She was the housekeeper to the Arbulus and as an exchange for her work, the Arbulus paid my grandmother with room and board. In a tiny room occupied by only a bunk bed, my grandmother, my uncle, my aunt, and my mom all slept together. Two at a bed.

As the years passed, my grandmother instilled two important life lessons into her children: work ethic and humility. Growing up in a house that was not theirs, wearing clothes that didn’t meet their peer’s standards, and standing at the welfare line for extra food became both the reason and the motivation to seek a better life, and to seek more opportunity. When the time came, it was in that same crammed up house that my uncle’s opportunity for a better life would present itself.

Photo: Courtesy of Johanna Ferreira

When he was 23-years-old, Coco found himself desperate and afraid. After leaving the Peruvian military, he was working as a cab driver in Peru and knew he needed something different. He deserved more. It was then that Cesar Arbulu, the grown son of the family that provided my grandmother and her children a home, offered him a way out. Cesar Arbulu was Peruvian with American citizenship, who traveled from the U.S. to Peru. He was a Vietnam veteran for the American army and following the years after the war, Cesar developed a few illnesses including alcoholism. Cesar told the U.S. government that my uncle was his caretaker and with that and a tourist visa, my uncle was allowed in the country for only six months. But he didn’t leave.

Coco still remembers his 1979 trip to the Peruvian airport. Cesar’s father told my uncle that he didn’t have what it took to make it in the United States. He told him he would fail because he was too quiet, he was too gentle. But it was those characteristics that allowed my uncle to immigrate successfully and then bring his family.

“I kept quiet. I minded my business. I worked hard and I prayed a lot,” he told me.

He told me that when you arrive you know it will be hard but that no plan you set in motion can prepare you for the trauma, or feeling inferior because you look different, because you speak different, because you are different.

“I was confused, nervous, insecure, scared. I never got comfortable because it’s not easy to immigrate. There’s a lot of hardship that comes with the journey of being an outsider. You experience a lot of trauma. Authority looks at you as if you are a criminal. I was illegal. But I wasn’t dangerous,” he added. “I wasn’t a criminal. You are racially profiled all of the time. My thick accent caused a lot of issues. I dealt with a lot of racism. Here I was, doing something great and yet, I was always ashamed. I didn’t feel good enough.”

Photo: Courtesy of Johanna Ferreira

My uncle was undocumented for six years. For six years he cleaned tables, he worked as a bell boy at a hotel and he parked cars as a valet. He made $2.65 an hour. He didn’t go out, he didn’t date, he didn’t socialize. Partly because he was afraid of getting caught up in situations that may expose his immigration status, and partly because he was afraid of what that immigration status may do to his psyche. He knew many people who often got depressed, turned to drugs and alcohol, got caught up in crime and soon after got arrested. My uncle was a natural introvert.

And while people in his past said it was his personality that was going to make him fail, I believe it was his personality that helped him succeed. He went from home to work. Sometimes he would go to the movies alone. Sometimes he would get lost in books at the library. He met the right people who helped him find work and housing and for six years he maintained and held his breath until 1986 when Reagan signed the Amnesty Bill in 1986. For the first time, probably ever, my Uncle Coco was free to chase his dreams.

In the next 10 years, my uncle would bring my grandmother, my aunt, my mother, and her children. All of us lived as undocumented immigrants but with luck, or destiny (my uncle would tell you it’s luck, I say it’s destiny) we all became citizens.

Photo: Courtesy of Johanna Ferreira

He is still an introvert. He is a reasonable man and will tell you things like “life is not fair” or “that’s just the way it is” to make more sense out of situations that are senseless. But I believe it was written in the stars and God, the universe, or the Earth — whatever it was — trusted my uncle Coco to change our lives for the better before we even existed. I believe there was a God that believed in his courage.

The soft-spoken man with gentle eyes trained his tongue to bend and move in foreign ways to learn a new language. He held on tight to his roots and culture while he assimilated with peers that looked nothing like him. In some of the loneliest times he must’ve had, he found the drive and will, understanding that the plan was far greater than just him.

My uncle reminds me that immigrants are heroes. That they are the epitome of courage. They are the bravest people you may know. Someone could call me an immigrant and it could never mean anything less than a recognition of persistence and bravery. It will always be an honor to know that resilience is in my bloodline.